Dual purpose

St. George and the Dragon

Book of Hours

France, ca. 1425

Illumination on vellum, 16th-century leather binding over wooden boards

Boston Public Library, Josiah H. Benton Fund, Ms.q.Med.81 (f. 132v)

[The page shown here is one of six from this Book of Hours on display.]

no. 8d

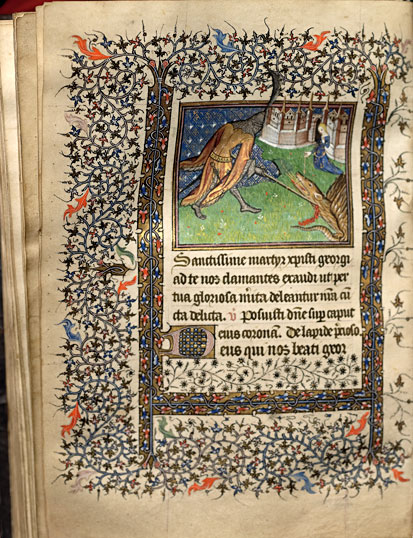

In the Christian context, slaying dragons is associated with St. George, as shown in this miniature which precedes a prayer to the saint. A terrible dragon, seen here in the lower right, ravaged the country around a city called Selena. Because its fiery breath poisoned the city whenever it approached, the people gave the dragon two sheep each day to satisfy its hunger. When sheep no longer served, human victims were required. They were chosen by lots and finally the lot fell to the king’s daughter. Dressed as a bride, the princess (upper right) awaits her doom but St. George (left), who was riding by, saves her by attacking the dragon.

A version of the story, reported in Jacobus de Voragine’s thirteenth-century Golden Legend, offers a Christian moralization of the tale, in which the dragon is taken as a symbol for the devil or sin: as St. George explains, people have only to believe in Jesus, receive baptism, and they will be delivered from the dragon’s ravages. The episode ends triumphantly as the Christian message successfully brings about massive conversions among the townspeople. The kernel of the story formed by hero, maiden, and dragon is particularly appropriate for a chivalric courtly culture, in which St. George becomes synonymous with knighthood. Not surprisingly then, St. George appears here as a knight errant saving a damsel in distress.

In the miniature, the kneeling lady is dressed in a blue robe with an elegant golden belt; she has long blond hair down her back, in conformance with the contemporary medieval ideal of beauty. She observes from the background, her figure placed against a walled castle (rather than the lake of the legend). Represented as a knight wearing an elegant gold robe with stylish long sleeves over his armor and a helmet whose rising plume extends beyond the frame, St. George plunges his lance deep into the dragon’s throat. Two triangular configurations serve to focus the eye on the action linking knight and dragon, and, then farther back, on the waiting lady. In secular romance, she and her castle are the customary prize for the knight’s heroic feats. This lady’s expressive gestures, with one hand extended and the other held close to her heart, signal her call for help as well as her attentive observation of the combat.