Published: February 2015

k

In fall 2013, students in history professor Marilynn Johnson’s undergraduate seminar “Making History Public” embarked on a study of Boston Common’s development over the past four centuries. Their investigations, assisted by research librarians at the Burns Library, generated an exhibition, from which the following text and images are taken. The exhibition is on display through May 2015 on the third floor of Stokes Hall South.

In 1722, before decades of landfill expansion shifted its position to the city’s interior, the Common was located at the edge of the Charles River. The map shows few trees on the Common, indicating the land’s focus as a place of work. Evidence of Boston’s strong shipping economy is seen in the numerous ropewalks—long buildings where strands of hemp fiber were formed into rope—located on the Common and elsewhere in the city. —Kelly Kren ’14

1722 map by John Bonner; courtesy of the Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the Boston Public Library

On June 19, 1656, Ann Hibbins was hanged on the Common for witchcraft. The wife of a wealthy merchant, Hibbins originally came to be seen as an unruly character when she sued carpenters over work done on her house, a case that she eventually won. During the trial, however, people thought she displayed an aggressive, un-Puritan personality. This resulted in her excommunication, and soon after her husband died many began to accuse her of witchcraft, which led to her trial and eventual conviction by the General Court. Hibbins appears as a fictionalized character in Nathaniel

Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (1850). —Kelly Kren

Ilustration by F.T. Merrill; from Lynn and Surroundings, by Clarence W. Hobbs (1886)

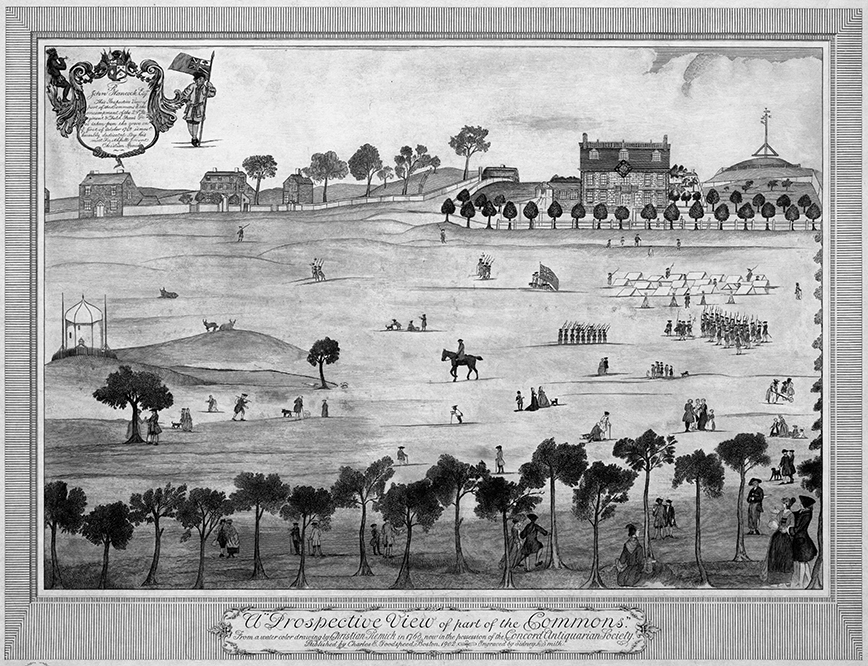

In the mid-1700s, as Bostonians increasingly came into conflict with Great Britain, the Common was transformed into a political battleground. Violent demonstrations convinced Parliament to send troops to Boston to keep order. On September 29, 1768, British soldiers of the 29th Regiment occupied the Common in a show of military might. A month later, they left for winter quarters. —Katherine Quigley ’16

A Prospective View of Part of the Common, a 1902 illustration by Sydney L. Smith, from a 1768 watercolor by Christian Remick; courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library

Boston Common is dotted with monuments and memorials, including the Crispus Attucks Monument and the Robert Gould Shaw Memorial. The Central Burial Ground, shown here, was created in 1756. Among those interred are British soldiers who died during the Revolution, American patriots from the Boston Tea Party and the battle of Bunker Hill, and the painter Gilbert Stuart, who is best known for his portrait of George Washington. —Emily Racette ’14

Photograph by Katherine Quigley

The uses of Boston Common changed dramatically over the centuries, but it has retained its most distinctive feature: that it exists for the people of Boston to use for the common good. From a cow pasture and place of daily productive activities, the Common became a leisure space where residents could enjoy quiet contemplation or more active entertainment. Cows were banned in 1830. —The class

1829 illustration by James Kidder; courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library

Although smoking was illegal in Boston during the 19th century, in 1851 the mayor established a Smokers’ Circle (for men only) on a small hill in the Common’s southwest corner. Here, according to Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, “scores of persons resort each afternoon and evening to inhale the bewitching weed.” —Sarah Finlaw ’14

Smoker’s Circle on Boston Common, an 1851 illustration by Fernando Edwards, from Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion

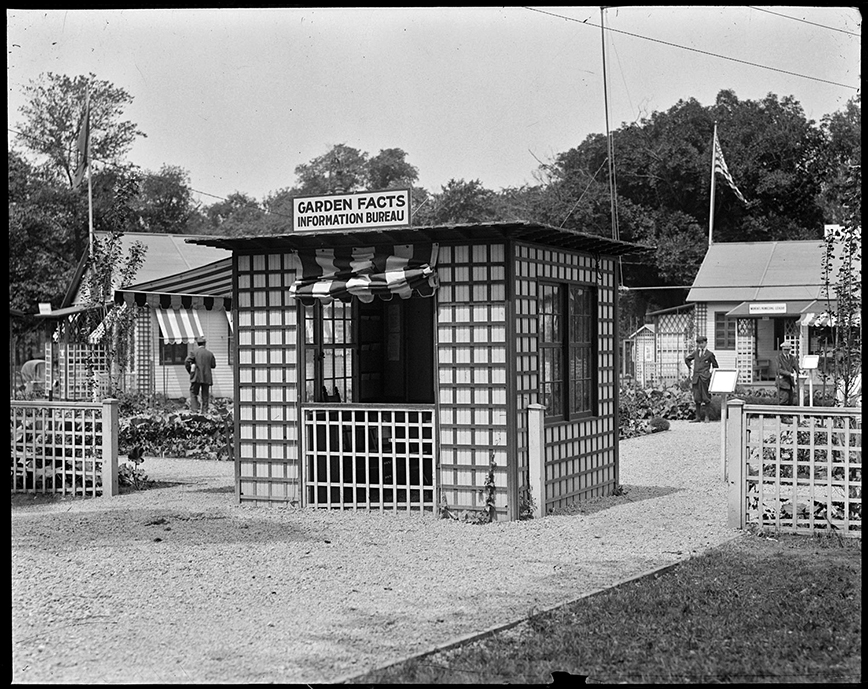

In times of war, the Common’s role has been modified to serve the federal government’s military objectives, from recruitment and training to war bond sales. War gardens, or victory gardens, such as this one were first established on the Common during World War I. In addition to producing needed vegetables, this facility provided information on how to cook and can certain foods. —Michael Fronte ’15

War garden entrance on Boston Common during war with Germany, 1918 photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

In July 1944, as part of the War Manpower Commission’s “Shot Out of the Sky” program, the wreckage of a German Messerschmitt Bf-109 fighter plane was displayed on the Common’s Parade Grounds in an effort to encourage war bond sales. —Michael Fronte

Messerschmitt displayed on Boston Common during World War II, photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

During World War II, the dome of the State House was painted black to prevent its use as a target during enemy air raids. Sections of the Common’s iron fence were torn down as the federal government enacted scrap metal drives. —Michael Fronte

Parks department collecting scrap on the Common, circa-1942 photograph courtesy of the Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

Throughout the 20th century, the Common was a popular location for soapbox orators expressing a wide range of views and ideologies. In the early decades of the century socialists, communists, and anarchists preached from perches along the Charles Street side of the Common, such as in this scene of a February 1931 socialist gathering. —Chris Cataldo ’15

Crowd Listening to a speech by a “Red” on Boston Common, 1931 photograph courtesy of The Trustees of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection

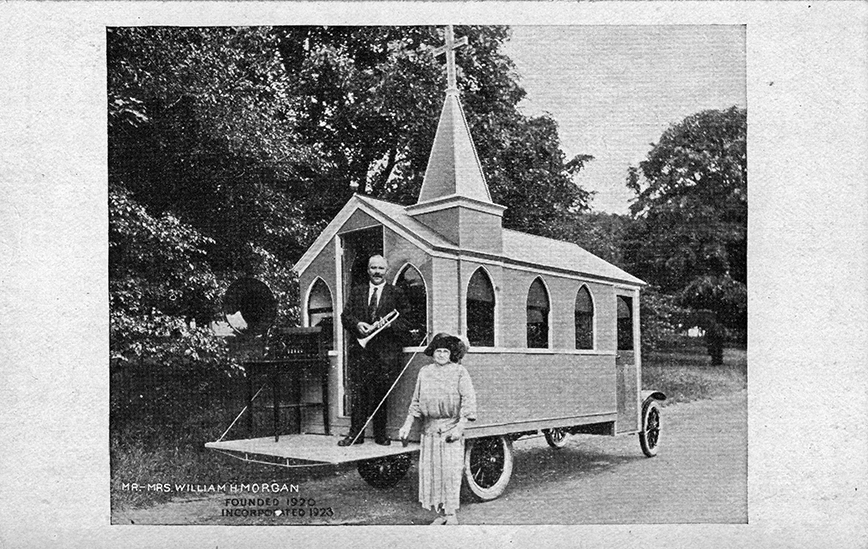

William and May Morgan outside their “Little Church on Wheels,” circa 1920. From this threshold, the Morgans proclaimed the Gospel to passersby on the Common. In 1938, they moved their ministry indoors, becoming the Emmanuel Gospel Center in Boston’s South End. —Roberto Martinez ’15

Photograph circa 1920, from a postcard

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Common was the setting for antiwar demonstrations. In the summer of 1968, large numbers of youths camped out on the Common. The City instituted a curfew to prevent them from sleeping in the park overnight. In December 1968, a judge from the Suffolk Superior Court ruled the curfew illegal. —Chris Cataldo

Photograph from May 5, 1970, by Joseph Dennehy, courtesy the Boston Globe Archive

Members of the “Making History Public” class met with Friends of the Public Garden founder Henry Lee in September 2013. From left, Kelly Kren ’14, Emily Racette ’14, Sarah Finlaw ’14, Katherine Quigley ’16, Chris Cataldo ’15, Lee, Ted Fockler ’14, Nate Fischer ’15, Michael Fronte ’15, and Roberto Martinez ’15.

Photograph by Marilynn Johnson